Etching Egypt’s History: The High Dam

Helmy’s artworks depicting the Aswan High Dam are among the finest of her etchings. They are also enduring reminders of the sacrifices Egyptians made in the pursuit of national ambition.

The Art of Menhat Helmy is a newsletter and platform supported by its readers and managed solely by the artist's family. Our goal is to persist in showcasing Helmy's groundbreaking artwork and to inspire emerging Arab artists.

If you haven't already, we encourage you to consider becoming a paid subscriber.

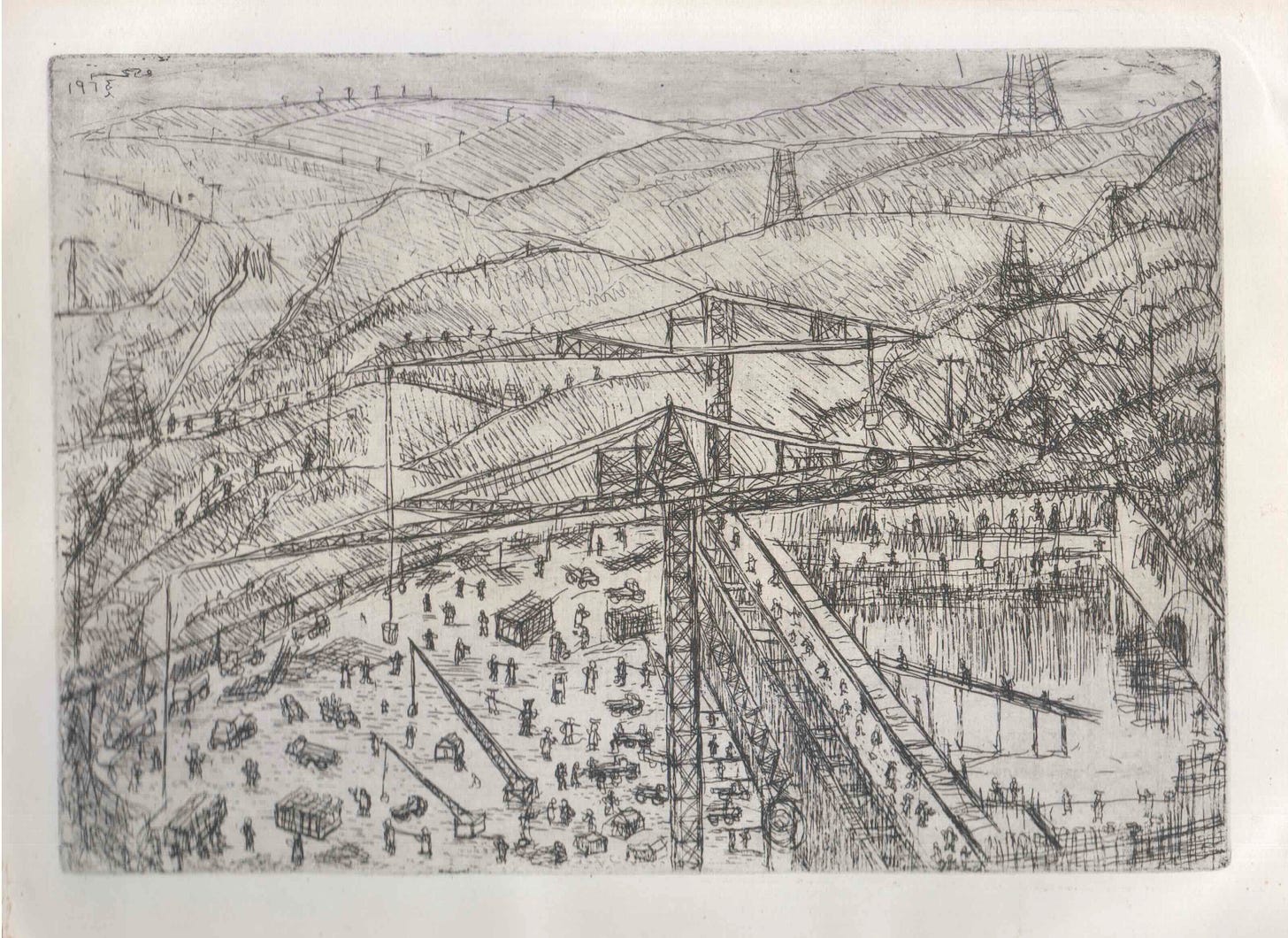

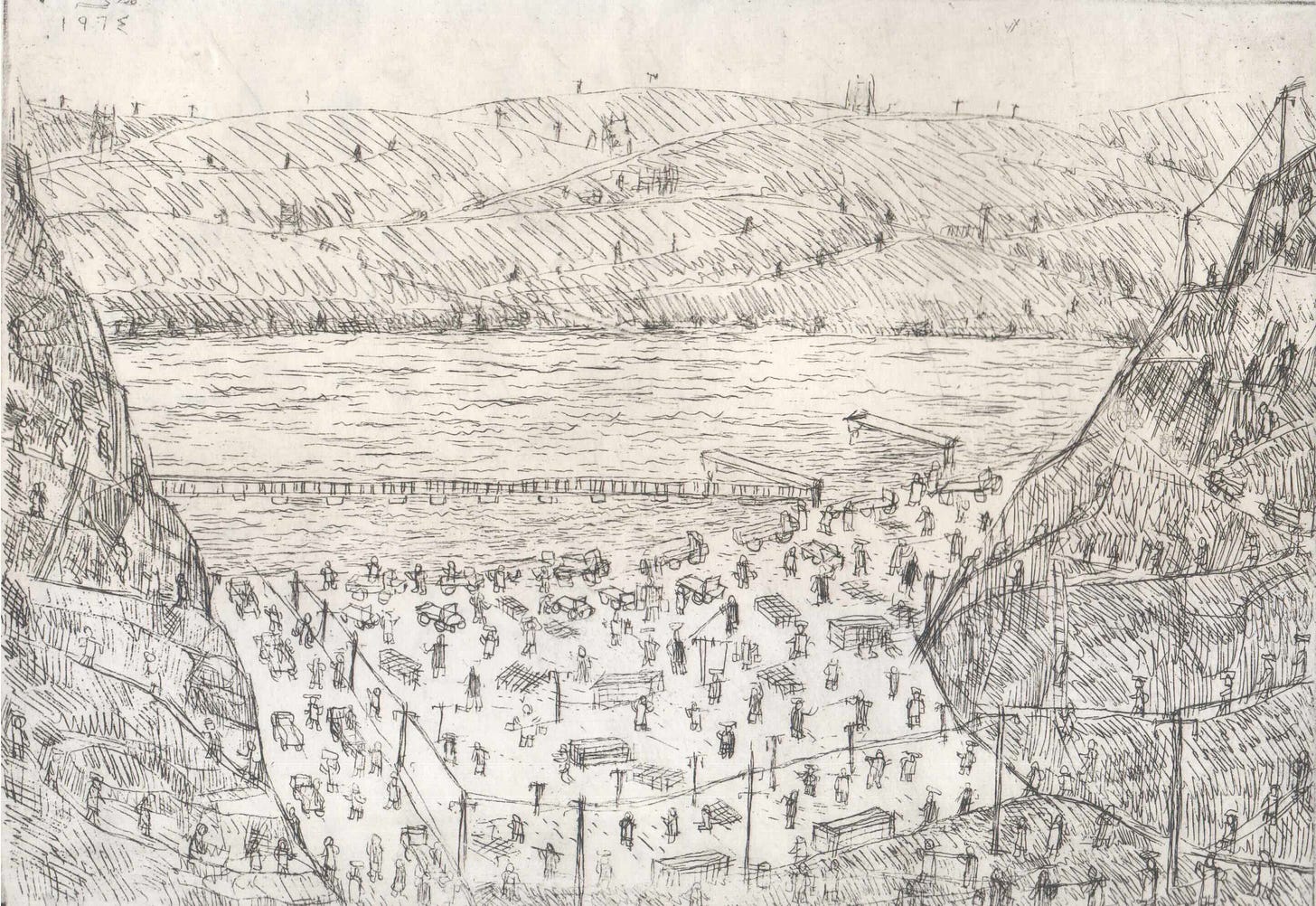

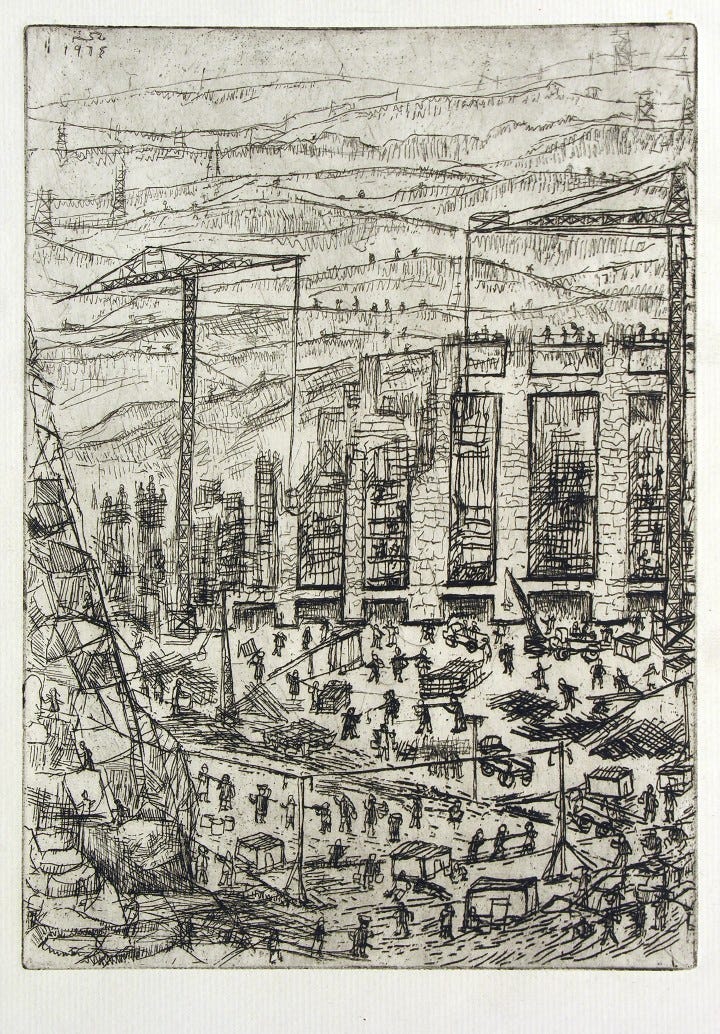

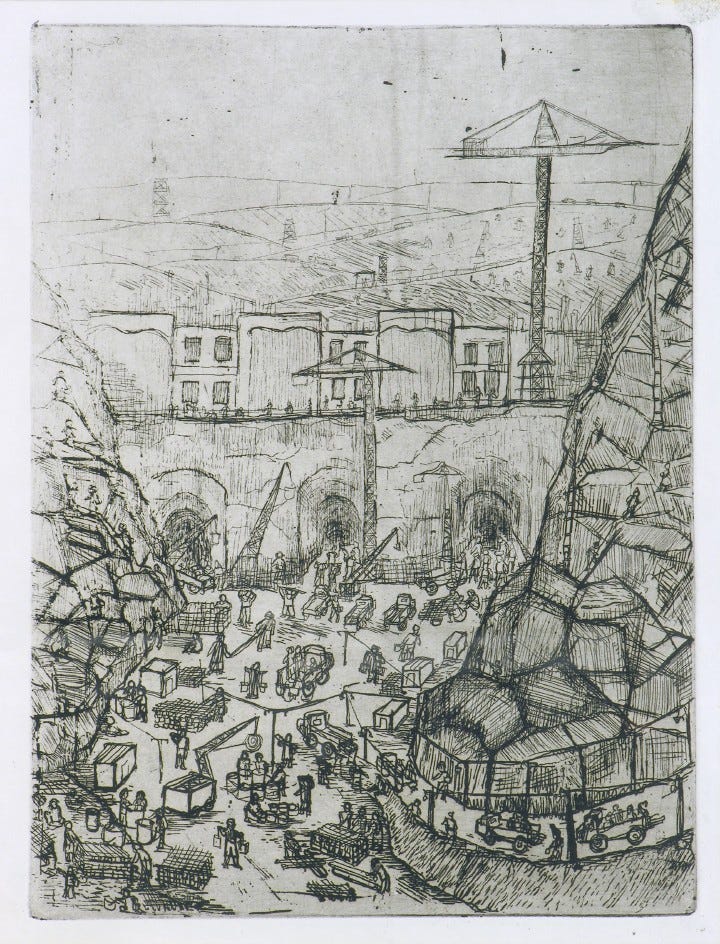

The pit is large and intimidating — a circular platform filled with towering cranes and flowing cement. Electrical stations pepper the rocky terrain while makeshift paths carve their way through the landscape. There are people within the pit — hundreds of workers as active as ants building their home. Some drive trucks while others labour in the smouldering heat, hundreds of kilometres away from their families.

This is the building of the Aswan High Dam as artist Menhat Helmy saw it in 1966. For her, the ambitious project was both a monumental achievement and a national sacrifice that came at the expense of Egypt’s poor.

Helmy was not alone in this view. The pioneering printmaker was one of several artists who travelled from Cairo to Aswan to document the building of the dam during the 1960s. Some, including Effat Naghi, Ragheb Ayad, and Tahia Halim, were given government grants to travel to the construction site in the hopes that they would return with favourable interpretations of the precarious project. While some artists did present glorified works that praised the construction, others (such as the aforementioned artists) opted instead to provide critical insight into the geographic and socio-political consequences that arose from the mega-project.

These artists were among the Egyptian intellectuals who rejected the Egyptian government’s thinly-veiled attempt at state propaganda, instead using their talents to challenge the government’s project and document the casualties it engendered. Thanks to these artists and their subtle artworks, we are now able to view the construction of the Aswan High Dam through their critical lenses.

“The Eighth Wonder of the World”

When Napoleon entered Egypt with his occupying French forces in 1798, he observed, “If I were to rule a country like Egypt, not a single drop of water would be allowed to flow into the Mediterranean” (Biswas, 25; Building the World, 612).

Since then, the River Nile has held a mysterious attraction to politicians from across the world, many of whom have attempted to assume control of its flowing waters. This form of hydropolitics — politics based on water resources — is the primary reason why the Aswan High Dam was developed in the 1960s.

When the Free Officers Movement overthrew the Egyptian monarchy in 1952, they became convinced that the Nile’s water had to be stored in Egypt, instead of the proposed Nile Valley Plan which would have stored water in Sudan and Ethiopia, for political control of water supplies. In 1958, the USSR sent support for the High Dam project, including technicians and heavy machinery.

The Aswan High Dam was promoted as the world’s largest embarkment dam, and became a key component of Gamal Abdel Nasser’s tenure as President of Egypt (and later the United Arab Republic with Syria). It was viewed as a symbol of Egyptian independence and industrialization due to its projected benefits, including the ability to generate hydroelectricity, increased water storage for irrigation, and control over Nile waters. As such, the Dam had a profound effect on Egypt’s economy, as well as its culture.

Construction of the mega-project commenced on January 9, 1960, and continued until July 21, 1970. The first dam construction stage was completed in 1964, and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev visited Aswan alongside Nasser to witness the ceremony to divert the Nile. It was on this occasion that Khrushchev referred to the Dam as the ‘Eighth Wonder of the World.’

And yet, despite the expected benefits propagated by the Egyptian government, the High Dam came at a hefty expense, including the forced displacement of over 100,000 Nubians residing in Upper Egypt. Many archaeological sites were also submerged by flooding, including the Buhen fort and the Fardus cemetery. There was also little reporting or documentation of the poor working conditions endured by labourers on the project.

It is here that Egypt’s artists played an invaluable role as eyewitnesses, observing the ongoing scene before projecting it back onto their preferred medium.

Countering State Propaganda

The early years of Nasser’s presidency were a time of national pride and hopeful expectations for the future. For the first time in a millennia, Egypt was ruled by Egyptians — an achievement that led many to become staunch Nasserists and near-propagandists for a state they believed to have set them free. This included artists such as Hamed Ewais, a friend of the president who was known as a pillar of revolutionary art in Egypt for works such as Al Zaim w Ta’mim Al Canal (painted in 1957 following the nationalization of the Suez Canal) and Le Gardien De La Vie (painted right after the Arab defeat at the hands of Israel in 1967).

Another example was Abdel Hadi Al Gazzar — once jailed by King Farouk for insulting him in the artwork The Popular Chorus — whose painting, The Charter (1962), depicts a green woman wearing a crown and holding Nasser’s manifesto while workers kneel before her.

When Nasser rose to power in the years following the 1952 coup d’état led by the Free Officers Movement, he was cognizant of the strategic advantages of cultural initiatives such as music, art, and literature, especially as state propaganda aimed at fuelling nationalist fervour and enhancing his populist government. In 1958, he founded the Ministry of Culture and National Guidance, which was responsible for funding and promoting Egyptian culture. Thereafter, the state maintained a guiding hand over Egyptian culture, swaying it towards nationalistic topics for creative expression that would then trickle down to the masses.

An example of the state’s influence in propagating political art came in the 1960s when the Egyptian regime offered government grants for artists and writers to travel to the Aswan High Dam construction site as it progressed. Among those who attended the various trips were Seif Wanly, Hussein Youssef Amin, Saad al-Khadem, Effat Naghi, Rageb Ayad, Tahia Halim, and writers Son’allah Ibrahim, Kamal al-Qilish and Raouf Musa’ad. Others who decided to independently venture to the High Dam included Menhat Helmy and Gazbia Sirry.

While some of these creative talents followed the government’s expectations for the commissioned work and documented the building of the Dam in all its glory, others attempted to maintain their independence and offer critical insight into the negative aspects surrounding the mega-project.

Tahia Halim (1919-2003) focused her efforts on depicting life in Nubia before its villages were drenched by Lake Nasser during the construction process and its inhabitants deported to Kom Ombo and other locations in 1962. Her paintings at the time were dream-like and inlayed with folkloric mysticism, highlighting the sadness at the fate of the beautiful land.. Two such works include In the Old Nubia Town and Boat Trip (1966).

Gazbia Sirry (1925) took a similar approach during her time in Aswan. Instead of documenting the High Dam itself, she took an interest in Nubia and took to painting colourful houses and life within the villages. A notable example is her Portrait of a Nubian Family (1962), now part of the Barjeel Art Foundation collection in Sharjah, UAE. The painting features a Nubian mother with four children, all of whom are wearing blank expressions on their faces, as though they had already accepted their inevitable fate.

Avant-garde artist Effat Naghi (1905–94) focused on the High Dam construction to produce paintings that did not even feature human subjects. Instead, the High Dam was the central figure — a precarious creation highlighted by sharp black lines representing the scaffolding and steel beams used to erect the monstrous and haphazard structure. There is little to inspire viewers within the piece, instead raising questions about whether Naghi intended to praise the Dam construction or criticize its unnatural aims. The work, entitled ‘The High Dam,’ was completed in 1966.

Interestingly, some of the artists who were not commissioned to document the High Dam construction were among those who produced some of the most detailed depictions. Menhat Helmy (1925-2004) ventured to Aswan at her own expense to witness the construction process, and produced four black-and-white etchings and a painting that encapsulate the historic moment in brutal honesty. Two of those works — The Deal & The High Dam — were created in 1964, while the latter pair — Workers at the High Dam & Electrical Station — were completed in 1966.

Not only are Helmy’s artworks depicting the High Dam among the finest of her etchings, they are permanent reminders of the sacrifices Egyptians made in the pursuit of national prosperity. Her art is filled with toiling workers — clogs in a well-oiled machine — who few remember in hindsight. And yet, Egypt’s unseen majority continues to live on in her work.

Egyptian novelist and short story writer Son’allah Ibrahim took a different path through his writing, one that led to two dichotomous books. The first was a book of state propaganda reportage done with his colleagues Kamal al-Qilish and Raouf Musa’ad titled The Man of the High Dam (1967), while his second book on the construction, titled August Star (1973), was chronicled his trip to the High Dam site in 1966. The second book, written while Ibrahim was studying in Moscow, is far more critical of the regime and the construction process.

These two books offer us insight into the self-censorship that impeded creative works due to the politicized nature of the topics, mainly the propaganda apparatuses that thrived at the time. Years later, Ibrahim commented on this aspect of his books:

“My friends and I wrote a travel book in haste about our experience…from the title of the book alone it is clear that neither in its language nor in its construction does it differ from the exalted propaganda of the time…I was simply doing what I considered to be my duty, telling myself that later I would…find an opportunity to express myself more freely.”

While it is true that plenty of artists found ways to be implicitly critical about the Aswan High Dam and stood up to Egypt’s thinly-veiled attempt at state propaganda, it should also be noted that none of these aforementioned works (apart from August Star, which was banned in Egypt) had any significant political impact. In truth, Egyptian art had limited scope at the time and was viewed as an elitist or intellectual platform rather than an outlet for the masses. As such, the critical works had little effect on the nationalist fervor that emerged during the construction process.

Although the artists were unable to reach a wider audience with their message, their works continue to live on to this day as analytical and historical documentation that allows us to reevaluate the societal and cultural context surrounding the High Dam.

Without these artistic depictions and writings, our understanding of the High Dam would be limited to propaganda and censored drivel instead of an honest, self-reflective evaluation of our historical wrongdoings.

The Art of Menhat Helmy is a newsletter and platform supported by its readers and managed solely by the artist's family. Our goal is to persist in showcasing Helmy's groundbreaking artwork and to inspire emerging Arab artists.

If you haven't already, we encourage you to consider becoming a paid subscriber.