Sugar Dolls

Ceremonial sugar dolls that were once the highlight of festivities to celebrate the Prophet Mohammad's birthday (al-Mawlid) in Egypt. Menhat Helmy's etchings are a reminder of the long-lost tradition.

The Art of Menhat Helmy is a newsletter and platform supported by its readers and managed solely by the artist's family. Our goal is to persist in showcasing Helmy's groundbreaking artwork and to inspire emerging Arab artists.

If you haven't already, we encourage you to consider becoming a paid subscriber.

When Menhat Helmy was a young, carefree girl in the 1930s, she was among the countless children across Egypt who eagerly awaited the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday—al-Mawlid al-Nabawi—to enjoy the delicious treats that marked the occasion. Perhaps none were more eagerly anticipated than Arousat al-Mawlid: the ceremonial sugar dolls that served as the highlight of the festivities.

Traditionally made with sugar and water, the dolls would be molded into the shape of a woman before being bedazzled in colourful bridal gowns and headpieces. They decorated sweet shops across the country in a deeply-rooted historical tradition that dates back to the Fatimid era (909 to 1171 AD). And when the children finally got ahold of them, they broke the dolls into pieces to consume the sweet treat.

As my grandmother grew into a young artist, she never forgot about the sugar dolls. Some of her first etchings after completing her studies at the Slade School of Fine Arts in London depicted the festivities and the sugar dolls.

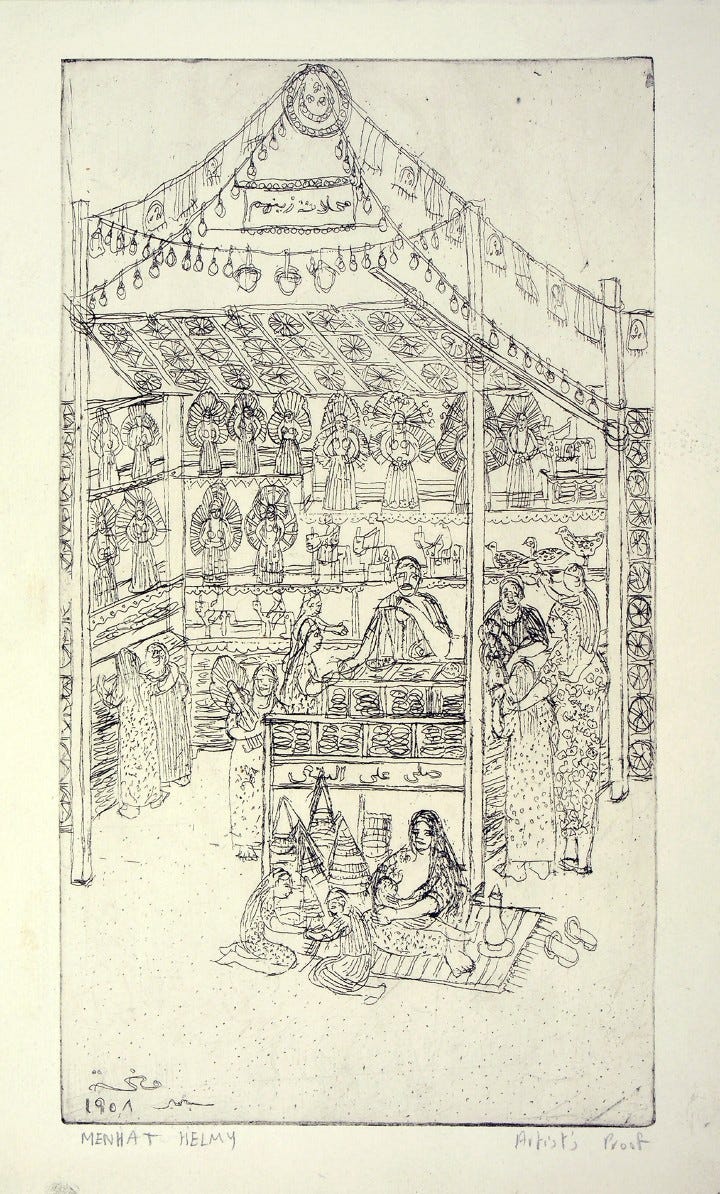

The above etching, dated September 1958, depicts a shop named “Zeinhoum’s Stores” selling a range of sweets including the renowned sugar dolls, which line flank the sellers. Children can be seen eyeing and purchasing the dolls, some accompanied by their parents. In front of the store lies a woman in traditional conservative clothing breastfeeding in public. While depictions of the Mawlid were not rare in modern Egyptian art, depictions of breastfeeding were. Helmy was among a small cohort of artists, including her contemporaries Gazbia Sirry and Inji Efflatoun, who embedded their art with such intimate acts, bucking norms and traditions that labeled public breastfeeding as taboo.

Helmy’s decision to depict breastfeeding in a scene with Mawlid dolls also carries some interesting symbolism, signifying both motherhood, childhood joy, folk traditions and fertility. Consider the origin tale of the sugar dolls. Historians passed a tale in which on a one specific Mawlid celebration, the Fatimid ruler Ba’amrUllah, dressed up as a soldier while riding a horse and went into the town with his wife along his side. She wore a dazzling white dress with a flower crown on her head. When candy makers saw the beauty of the ruler’s wife, they decided to include her in their depiction, launching a tradition of doll making that would stand the test of time.

Another tale from the Fatimid era promised that soldiers returning from war would be rewarded with beautiful brides for their bravery. Both origin stories frame women as objects of desire and as rewards for masculine prowess. By depicting a conservative woman breastfeeding in front of the sugar dolls, Helmy may be subverting this tradition, offering a more contemporary vision of female empowerment and beauty. She could also have believed, as some experts did, the Mawlid doll is actually tied to the goddess Isis and celebrations of fertility and life.

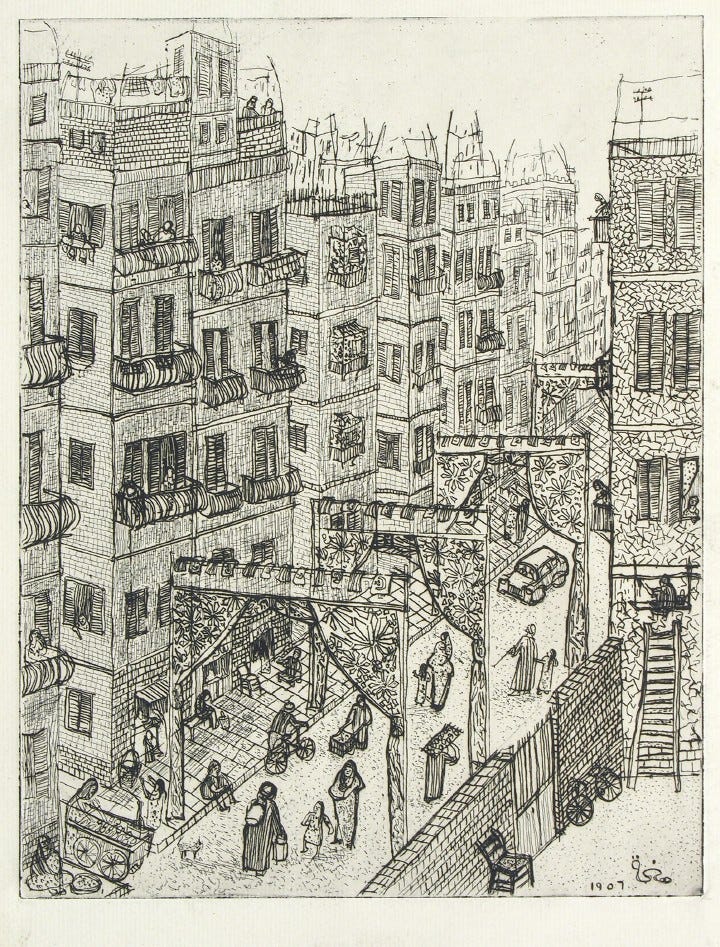

Helmy’s etchings have also come to depict a bygone Cairo—snapshots of a city that no longer exists in that form. Even the sugar dolls, once a highlight of al-Mawlid festivals, are slowly dying out. But in many shops the edible sugar doll has been replaced with a plastic version, especially in larger cities like Cairo. They are more profitable but lack the creative and artistic flair of their sugary counterparts. Even the public spaces once decorated with colourful ornaments to mark the festivities seem to have disappeared.

In 1956, Helmy etched a scene in a the Bulaq region of Cairo depicting the celebration of the birth of Egyptian Sufi writer and poet Salama Hassan Al-Radi. The founder of the Sufi order Al-Hamidiyah Shadhiliyya, al-Radi was a celebrated figure of the sect, especially in Egypt. His shrine was regularly visited by devoted Sufis and the anniversary of his birth—the mawlid—was celebrated, especially in Bulaq. These scenes no longer exist in Cairo, both because Bulaq has been gentrified over the years and because Sufism’s influence has weaned in comparison to more radical ideologies like Wahhabism, which forbade the visiting of shrines or the celebration of religious figures.

While my grandmother could not have known just how much her beloved city would come to change, her work serves as a snapshot of better times — a bygone age when Egypt’s sprawling capital was defined by its people, not its monuments.

The Art of Menhat Helmy is a newsletter and platform supported by its readers and managed solely by the artist's family. Our goal is to persist in showcasing Helmy's groundbreaking artwork and to inspire emerging Arab artists.

If you haven't already, we encourage you to consider becoming a paid subscriber.