A Portrait of an Egyptian Artist in 1950s London

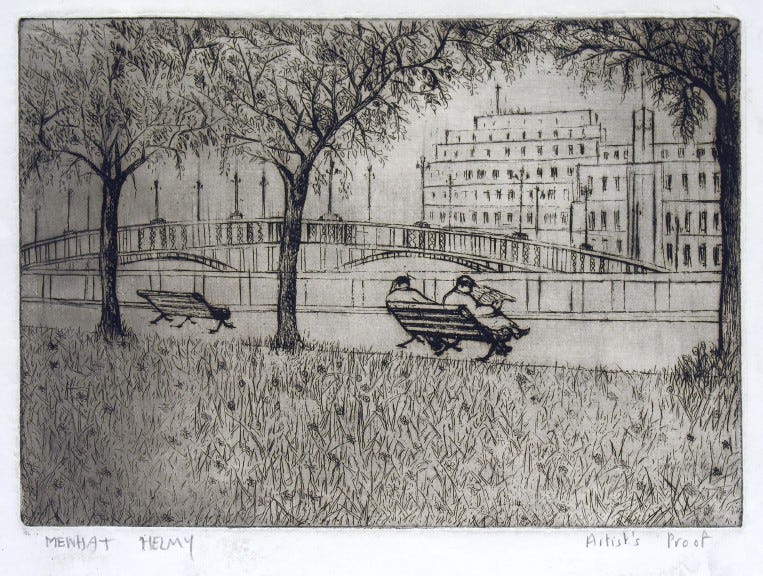

On the occasion of Menhat Helmy's 100th birthday: A fictional retelling of her final year at the Slade School of Fine Arts, written by her grandson Karim Zidan.

The Art of Menhat Helmy is a newsletter and platform supported by its readers and managed solely by the artist's family. Our goal is to persist in showcasing Helmy's groundbreaking artwork and to inspire emerging Arab artists.

If you haven't already, we encourage you to consider becoming a paid subscriber.

“So how exactly does one pronounce your name?”

Menhat had heard this question before. She had her answer memorized by now but it did not matter. The British never got it right.

“It’s Menhatulla Helmy — as in Men-hat-allah — but you can just call me Menhat.”

The man blinked twice and she could almost see him struggle to register the word behind his pencil-thin moustache and British sensibilities. “Menu-hat, is it? What a charming name. I’m Anthony Gross and I’m delighted we finally have a chance to meet. Bill — I mean Professor Coldstream — brought up your name after I took over as head of the printmaking department so I wanted to meet our only Egyptian etcher,” he said, his moustache stretching as he smiled.

Menhat sat up in her seat, a thousand thoughts flooding her mind. The office seemed to be shrinking in size. Expectations worth their weight in gold settled over her. She forced herself to smile and fiddled with her skirt, which bought her a few seconds to regain her composure. “That’s very kind of you, Mr. Gross. Is there something in particular you would like to talk about?” she asked.

“Let’s start by looking through your portfolio. Bring it here if you don’t mind.”

The heavy beige folder exchanged hands. Mr. Gross untied the knot and opened it with the care and precision of a trained artist. Menhat watched the balding man sift through the artworks, separating each paper and arranging it across his desk. He put on a pair of glasses, occasionally picking up one of the delicate sheets to examine the etching.

Mr. Gross sat back in his chair and lit a cigarette. He did not talk for several minutes, instead choosing to gloss over all the works before him, as though he were attempting to solve a puzzle. Finally, he finished the cigarette and looked up at Menhat. A hint of a smile marked his face.

“You’ve certainly got an eye for detail. Your hand is a little shaky in places and some of the earlier ones are already fading due to poor printing but this is quite something. Did you do any printmaking in Cairo before coming to Slade?”

“No, sir. I actually learned it here. I didn’t want to take architecture or sculpture so I decided to try design. Then I discovered etchings and feel in love with it.”

“Yes, I can see that. Is that Carisbrooke castle?” he said, pointing towards a small print near the edge of the desk.

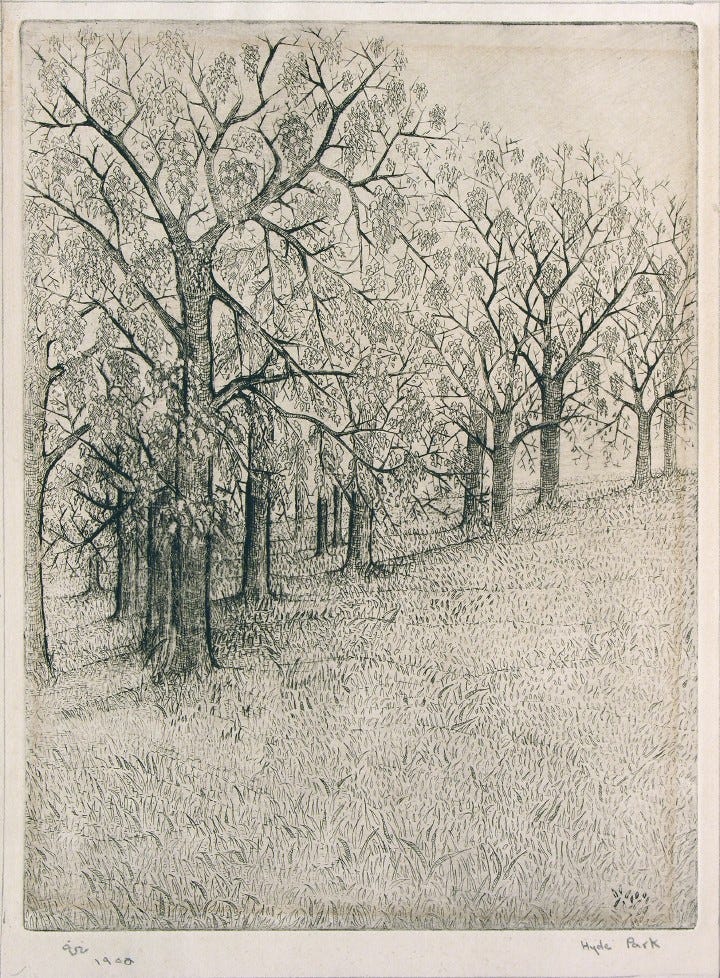

Menhat nodded. “Lovely. Glad you’re trying your hand at aquatint. Really gives those lines some depth when capturing scenery,” he said.

Mr. Gross continued to pull artwork out of the portfolio — sketches, drawings, and a couple of unstretched canvases with her nude model studies from the life drawing class. And yet he seemed to be captivated by the etchings, his fingers gliding over the cotton paper in short, delicate strokes as he examined the works.

“Did you create these works from pictures?”

Menhat shook her head, “I walk around the city — sometimes as close as Maple street or as far as the Isle of Wight. I take a sketch book with me and draw what I see in front of me. If I like it, I take it to the studio.”

“That explains the attention to detail. But what about this one?” Mr. Gross said, raising a small etching from the pile in front of him. Menhat cringed. There were black marks along the edges and the ink was faded. She could barely make out the fish swimming between the seaweed. A poor example of her work, she thought.

“I sketched that in the antiques room. They said I could draw anything in the room, and — well — I saw the fish tank in the corner and decided I preferred that over the old statues.”

“Ha! Bet they didn’t expect that?”

“Professor Coldstream didn’t know what to make of it, sir. Then when he introduced me to printmaking, I decided it would be my first print. As you see, it wasn’t a great one overall.”

“Yes, well, it certainly isn’t your best, but you capture England with a keen eye. I see why Professor Coldstream mentioned you,’ he said, leaning back in his seat as he lit another cigarette. ‘But do you know which one I’m particularly taken by?’

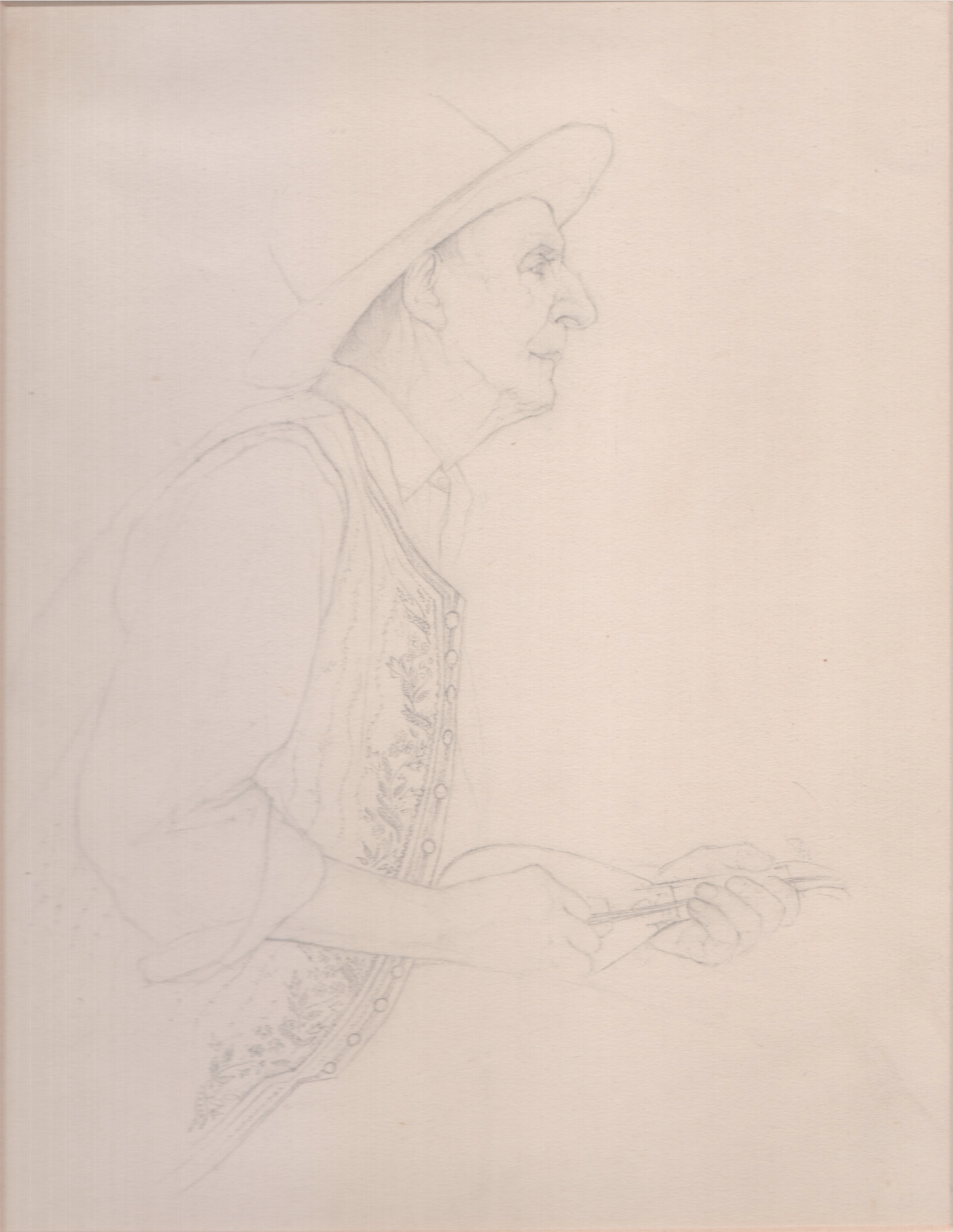

Mr. Gross pointed to the etching right in front of him. Menhat leaned over and saw a tall print she recognized immediately — The Kamman Player. She remembered that day well. Regent Park, 1954; it was a cloudy day and she was worried it would rain over her sketchbook. She took shelter beneath the hornbeam tree by the stream and continued to draw. She lost herself within her work, each line given equal attention.

Then came the old man with his fiddle. He appeared out of nowhere, dressed in a embroidered vest and a wide-brimmed hat which he tipped in silent greeting. He smiled and asked if he could sit on the bench beside her. Menhat nodded her head and returned to her work. Moments later, she found herself being carried away with the sounds produced out of the wooden instrument. The old man made his fiddle quiver with each note, creating layers of depth and grace that Menhat had not heard in several years. It was the sound of love and loneliness, of unbridled joy and heart-wrenching sadness. It was the sound of home.

Menhat watched the old man bring life to the spike-fiddle, with its ovular body and skewered neck, like the old masters in the Middle East. He rested the wooden instrument on his knee and held it up vertically, much like the kamman played back home. She was mesmerized by his song and soon found herself turning in his direction, her hand still cradling a pencil. She discarded her sketch for the time being and turned to a blank page and began to draw once more. She watched the old man work his magic and allowed her hand to be guided by the sound of his fiddle.

Minutes passed; shapes formed. First a head, then a face, nose, then came the body and the embroidered vest; finally, there was the fiddle, connected as though a part of the man himself. Done. She was pleased with the result and knew shew would be taking this one back to the studio to print.

The sun was beginning to set beneath the clouds. Menhat waited until the old man had finished his song and approached him with the sketchbook. She sat beside him on the bench and showed him the sketch. He laughed — a deep raspy sound unlike the vibrant tones of his fiddle — and asked her name. “Menhat Helmy,” she responded.

“Where are you from Menhat?” the old man asked, and she was shocked to find that he had pronounced her name correctly.

“Cairo.”

“Ahlan wa sahlan,” the old man said, now grinning from ear to ear. “Keif halek?”

The old man’s use of Arabic took Menhat by surprise. She had never encountered a foreigner outside of Egypt who could speak Arabic, let alone someone who could greet her and ask how she was doing. “Ahlan beyk,” she replied, though her tone was more reserved. “Where are you from, sir.”

“Armenia but I live in Lebanon — Anjar mostly,” he said, “I emigrated there from Musa Dagh almost 15 years ago. I sometimes come to London to visit my daughter. She is a citizen here now.”

“London is lovely,” Menhat said. “I’ve enjoyed my time in this city.”

“Yes, yes, me too,” he said, his eyes lingering over the nearby stream. He then turned back to Menhat. “But our countries are better.”

Menhat smiled. She liked the old man. He reminded her of her uncles back home. They sat in silence, meditating over his words and the slow trickle of water downstream.

“So what’s the old chap’s name?” Mr. Gross asked.

“Arto Sandaldjian.”

“Sandel-john — I feel like I know him already.”

“I wanted to ask, sir — what drew you to this etching? It isn’t as detailed as the others and I still haven’t finalized the prints.”

“It isn’t about the details, my dear. Looks at the man’s face — there is sadness there. You capture his loneliness as he performs and that is worth its weight in gold. You can etch all the scenery you want but none of that will compare to a few strokes of genius. Emotion, my dear. That is when you capture your audience and tell your story. You already do this with your painting — but now I challenge you to do so with your etchings.”

“I’ll do my best, sir”

“Excellent, excellent.”

Mr. Gross leaned back in his seat and lit another cigarette, exhaling plumes of white smoke above their heads. He looked across the desk at the student sitting before him as though he were taking her in for the first time. Menhat sensed him watching her, even though she kept her eyes fixed on the table.

“You know I spent some time in Cairo,” he said, breaking the lingering silence between them.

“Did you, sir?”

“Oh yes — I was a captain in the 9th Army during the war. Got stationed in Cairo for a few months in 1942 before moving on to Palestine, Syria and Lebanon; mainly painting the war and so on. Heaven knows I’m not a soldier. Then I was brought back again in 1942 from Tehran and spent time with the 8th Army — terrible business; witnessed the Battle of El-Alamein.”

Menhat remembered reading about the battle and listening to her father and elder cousins discussing it in their salon at home. She remembered the soldiers patrolling the streets as she walked to school. “Did you get a chance to interact with many Egyptians, sir?” she asked.

“Not many, no. But they were strong, able-bodied men from what I could tell. Not too bright but good soldiers when under the right leadership.”

Menhat smiled. Only the English could make insults sound like compliments. , “Hard to believe it’s been 10 years since the war ended.”

“And yet the British Empire is falling to pieces. Look at India or that Nasser chap in Egypt. It’s all well and good for countries to seek independence but where does that leave England? Even Churchill decided to take a bow and resign from office last month. Times really are changing.”

Menhat had never met a teacher quite like Mr. Gross. Professor Coldstream was a commanding figure; brisk, dapper, and always dressed in a suit, tie and waistcoat. Mr. Gross, on the other hand, was quick-witted and surprisingly blunt for an Englishman. There was no subtlety with this man, only charm and a fading sense of nostalgia. She did not know why, but she sensed she was free to speak her mind in front of this man.

“With all due respect, sir — maybe it is time for a change.”

“Ah, so you’re a socialist?”

Menhat sensed a rhetorical question. She smiled and let his words linger in the air, intertwined with the silver wisps of smoke.

“I think you’re a fine artist. And you have a good head on your shoulders. I want you to consider submitting an entry for the Slade Prize in Etching — you’re in your third year, right?”

“Yes, sir. I graduate in a few months, God willing.”

“Then that settles it. You’ll submit an entry. I think your work is as good as any student I’ve seen in their final year. Maybe even better. We’ll have to see, won’t we?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Right — that’s settled, then,“ Mr Gross said, rising from his seat. “I think that is enough talk of art and politics for one evening. It was a pleasure to meet you, Ms. Menu-hat.”

“The pleasure is all mine, Mr. Gross.”

The Arthur Tattersall House at 115-131 Gower St was a discreet, charming residence across from the Slade School of Fine Arts, and minutes away from Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Street. The brick facade glimmered deep red against the nearby lamppost, highlighting twelve large units wedged side-by-side in typical London constriction. Most of the school’s international students called it home.

Menhat’s room was fully equipped with the bare necessities. There was a kitchenette, a bed, telephone, and washbasin with a shower, and a table that doubled as a work station, which she kept beneath the small window overlooking the bustling street. She placed the portfolio on the desk and checked to see if her plants needed watering. They did and she needed the distraction.

Menhat avoided thinking about the meeting with Mr. Gross for as long as she could. She made some dinner — a cucumber salad and a bowl of peas and rice — and spent some time organizing her chest of drawers, making sure each item was folded in perfect squares. She then changed into a stripped nightgown and slipped between the warm sheets in her bed.

Her mind grew restless. She replayed portions of her conversation with Mr. Gross. The man was clearly knowledgable about etchings, the techniques, the history, and even the lore, but there was so much more to him. He was not stiff and self-righteous like many of his colleagues, instead exuding the casual air of a man who bucked traditions and unnecessary decorum.

She had heard about him before, of course. News spread quickly about his appointment as head of the printmaking department at The Slade, and so did the rumours about his life and travels. “Did you know he worked in film?” one student asked. “He did the art for all my favourite books,” said another.

Menhat had never read Wuthering Heights or The Forsythe Saga, or that new one that came out recently that everyone was talking about — Lord of the Flies, or something like that — but she was impressed. And now here he was, encouraging her to submit an entry into the school competition, and at Professor Coldstream’s recommendation, no less!

Before Menhat knew what she was doing, she climbed out of her bed and walked over to the desk. She opened the drawer attached to it and pulled out a folded letter, wrinkled from repeated reads. She sat beside the desk and read her Baba’s words beneath the moonlight:

My dearest Menhat,

I went out into the courtyard for a walk this morning. I took your mother with me, and together we strolled through the garden and had breakfast beneath the veranda. We watched the sun rise and were in awe at its beauty. Even at my age, it never ceases to amaze me — what a miracle it is! I watched it rise and settle on the mango tree, casting a shadow over the exact spot you used to sit and paint every evening after school. It might have been a trick of the light but I could almost see you there at that moment, putting down greens and reds and yellows and violets until the garden came to life on your canvas.

But, of course, you were not there. No, you are off on your own adventure. An artist groomed among masters. A free woman in a man’s world. My daughter raising the family name to new heights. I have no doubt that you will meet every expectation I have placed on you, as unreasonable as they may be, and surpass them with the grace, charm, and resilience that you could only have inherited from your mother.

I know that, by the grace of God, I will see you again in a few months. But I am not ashamed to admit that my heart aches in your absence. I may have seven daughters but each of you represents a portion of my soul. When any of you are away, I am incomplete. But alas, it is the will of God, and who am I to question Him.

I shall rest easy tonight knowing my beautiful Menhat is achieving her dreams and building a life of independence. This country needs strong women like you now more than ever. Things are changing, my dear, and you must rise up to the demands that come with it. Indeed, I know you shall.

Until we meet again,

Mohammad Helmy

Menhat had read the letter more times than she could remember now but it always blanketed her with a sense of calm. It was a reminder of what she had sacrificed, the friends and family she had left behind, and the goals she had set for herself when she got the government scholarship three years ago.

Tired, Menhat retreated to her bed. She slid between the sheets and closed her eyes, welcoming the empty black. Her muscles relaxed and soon she could imagine the garden in Helwan — her favourite place at home. She inhaled deep and got a whiff of the mango tree she loved. The smell soon vanished, replaced by the scent of attar — her Baba’s smell. She pictured him standing there — lean and proud in his suit and tarboosh, a king among men.

He smiled and she faded into the night.

The Art of Menhat Helmy is a newsletter and platform supported by its readers and managed solely by the artist's family. Our goal is to persist in showcasing Helmy's groundbreaking artwork and to inspire emerging Arab artists.

If you haven't already, we encourage you to consider becoming a paid subscriber.