Edvard Munch, Menhat Helmy, and the art of printmaking

The 12-storey MUNCH Museum houses more than 28,000 works by Edvard Munch, including 18,000 of the artist's prints. As the grandson of a pioneering Egyptian printmaker, I was touched (and jealous).

The Art of Menhat Helmy is a newsletter and platform supported by its readers and managed solely by the artist's family. Our goal is to persist in showcasing Helmy's groundbreaking artwork and to inspire emerging Arab artists.

If you haven't already, we encourage you to consider becoming a paid subscriber.

On a cool, drizzly Sunday in May 2025, I visited MUNCH, the museum dedicated to the life and works of the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944)—best known for arguably the most famous painting in the world, The Scream.

Located along the waterfront in the beautiful Norwegian capital of Oslo, the museum houses well over half of the artist's entire production of paintings and at least one copy of all his prints. This amounted to over 1,200 paintings, 18,000 prints, six sculptures, as well as 500 plates, 2,240 books, and various other items. Spread across 13 floors, the museum is considered to be one of the largest single-artist museums in the world.

Munch’s work is unique, evocative, and in some cases, irresistible to thieves. In fact, The Scream has been stolen twice. A version of the painting was stolen from the National Gallery in Oslo during the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, when two men needed just 50 seconds to steal one of the most famous paintings in history. Adding insult to injury, the thieves left a note scribbled on the back of a postcard that read: "Thanks for the poor security." The priceless painting was recovered a few months later after an undercover sting operation.

In August 2004, another version of “The Scream” was stolen, along with Munch’s “The Madonna,” this time from the Munch Museum in Oslo. Three men were convicted in connection with that theft in May 2006. MUNCH also received major upgrades in security, as safeguarding the artworks had become a matter of national importance. This was immediately evident during my visit. Large bags, umbrellas, and food were prohibited upon entry. Security personnel patrolled the galleries, with several stationed permanently beside Munch’s most famous pieces. Cameras monitored every angle, and motion detectors sounded if anyone ventured too close to the art.

Over the course of four hours, my wife and I made our way through the entire building, weaving between tourists, school groups on field trips, and artists sketching studies of Munch’s work. We saw all of Munch’s most famous works and were enchanted by the various eras and styles that made up his oeuvre. And though he is best known for his paintings, I was surprised to learn that he was also an prolific printmaker.

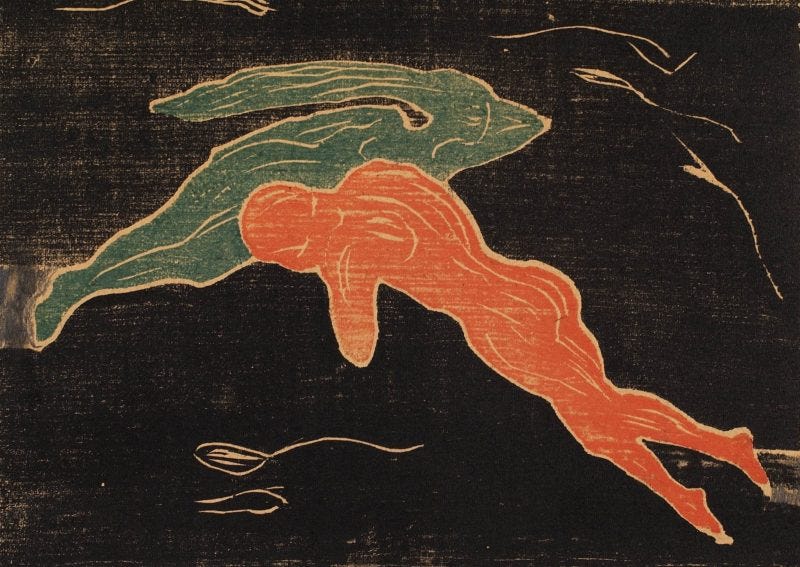

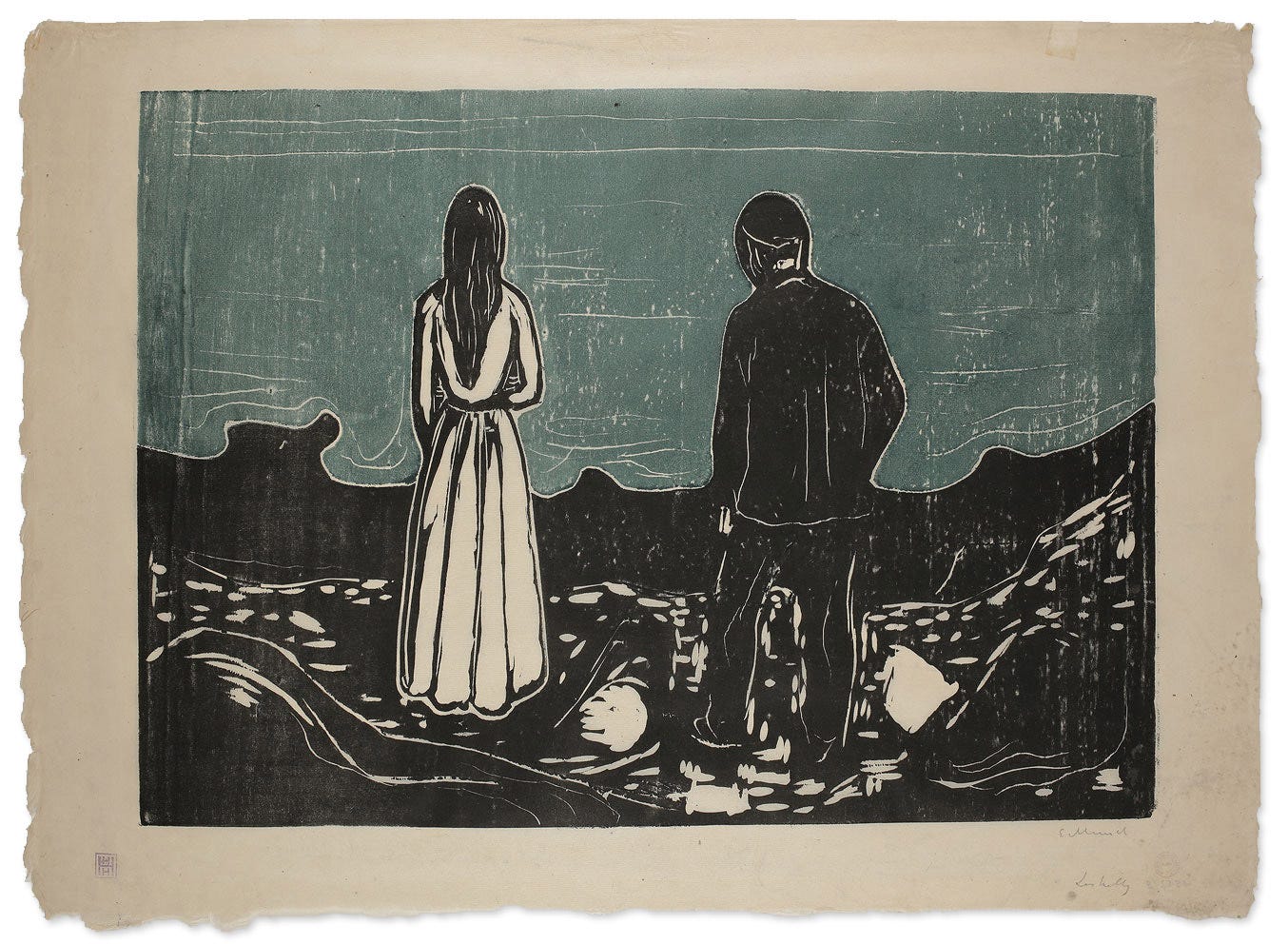

When the Norwegian artist first tried his hand at printmaking in the late 1800s, graphic works were becoming increasingly popular in the Western art scene. Berlin, where Munch resided at the time, was at the cutting edge of new printing techniques. He therefore began to experiment with lithography, etchings and woodcuts, eventually settling on the latter as his preferred medium.

Printmaking offered Munch the chance to rework and reprise elements from his earlier paintings, allowing him to experiment with various techniques that produced striking results. This was the case with The Scream, which Munch first painted in 1893 before attempting it in print form three years later. At the time, he called the print The Scream of Nature. I had the opportunity to see the print, as well as two other versions of The Scream that Munch painted, during my visit to MUNCH.

The various versions of The Scream—a painting, a drawing and a print—were housed in their own dimly-lit room in the museum. Since Munch had created each version on either cardboard or paper, they were more fragile than oil paintings on canvas. Therefore, the works alternated every 30 minutes; one is always visible while the other two others rest in darkness.

I learned much about Munch’s unique printmaking process on the floor dedicated to his graphic works. Munch had even donated his printmaking tools, as well as the plates, stones, and woodblocks he used to produce the work, none of which were destroyed as was the practice among professional printmakers. This is how researchers figured out his techniques, such as chopping up a wood block with a fretsaw before inking each segment separately, and then fitting them back together like a jigsaw puzzle.

Munch’s graphic works numbers close to 770 different prints. Moreover, the museum houses an astonishing 18,000 prints in total.

What I found most astonishing—and the reason I decided to write this essay—is the museum’s dedication to preserving and representing Munch’s prints. This level of institutional respect is rarely given to prints, which are seen as less grandiose and valuable than oil paintings. With Munch, there appeared to be a consensus that, while his paintings were grand and robust, his prints were intricate and expressive, sometimes revealing a deeper layer to the themes and motifs being discussed.

As the grandson of a pioneering Egyptian printmaker—one overshadowed by colleagues with a penchant for painting—I was touched by the exhibit and, quite frankly, jealous that the Norwegian government had dedicated such vast resources to studying and protecting Munch’s prints. The Munch museum has even digitized the entire collection.

During Menhat Helmy’s lifetime, printmaking was still a highly respected art form. Towering figures such as Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall, Joan Miró, Max Ernst, Lovis Corinth,Wassily Kandinsky, Andy Warhol and Paul Klee all experimented with various forms of printmaking in the 20th century. They, and countless other artists at the time, helped rejuvenate interest in an ancient practice that dates back thousands of years.

Printmaking also holds a rich history in the Arab world. From Mesopotamian stamp & seal printing to the 17th century lithography presses used to print high quality Qurans, the practice has played a variety of roles throughout the history of the region. However, many of Egypt and the Arab world’s most renowned artists during the 20th century likely learned the various printmaking techniques while studying abroad.

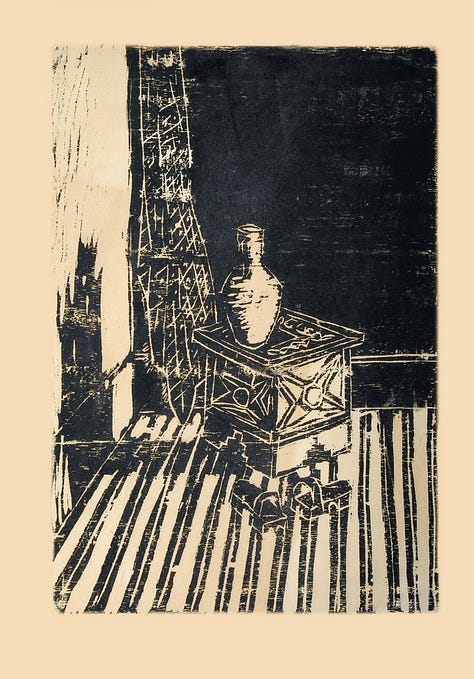

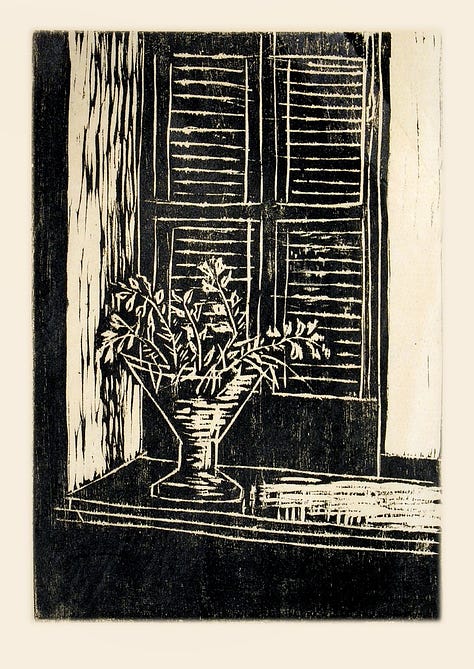

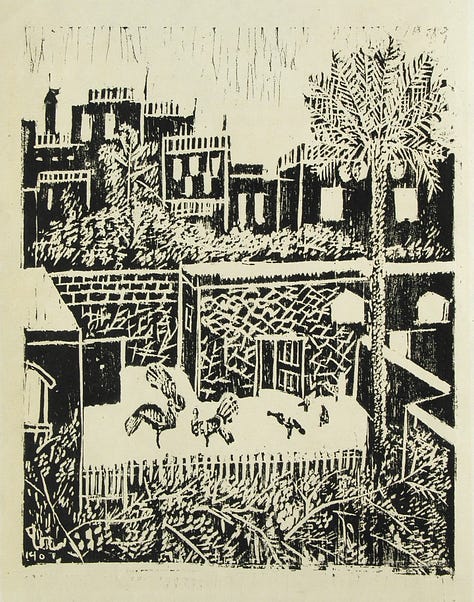

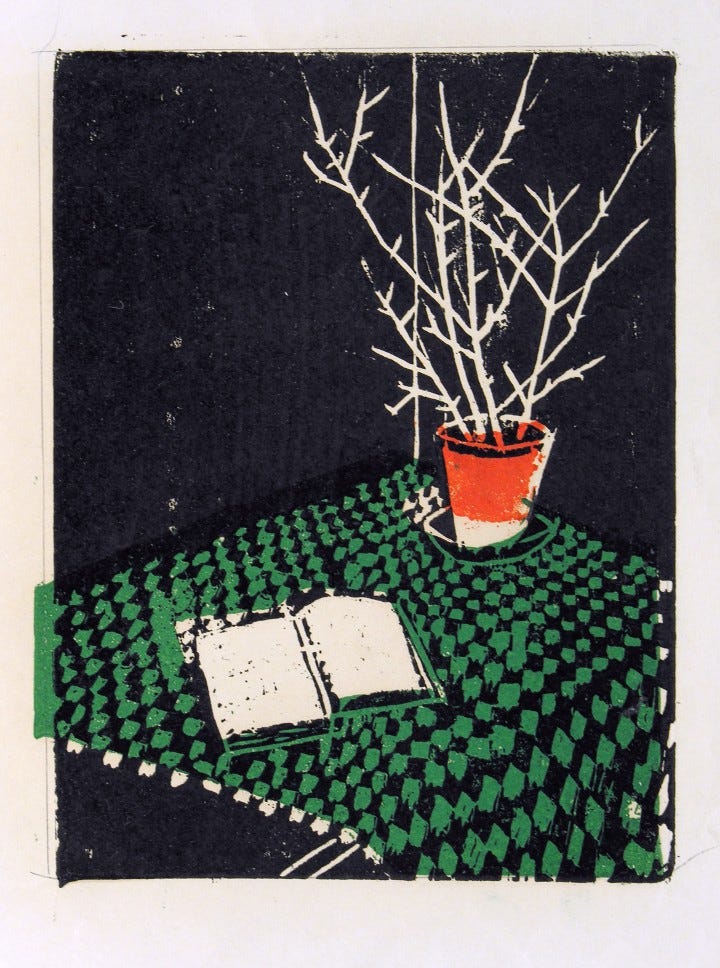

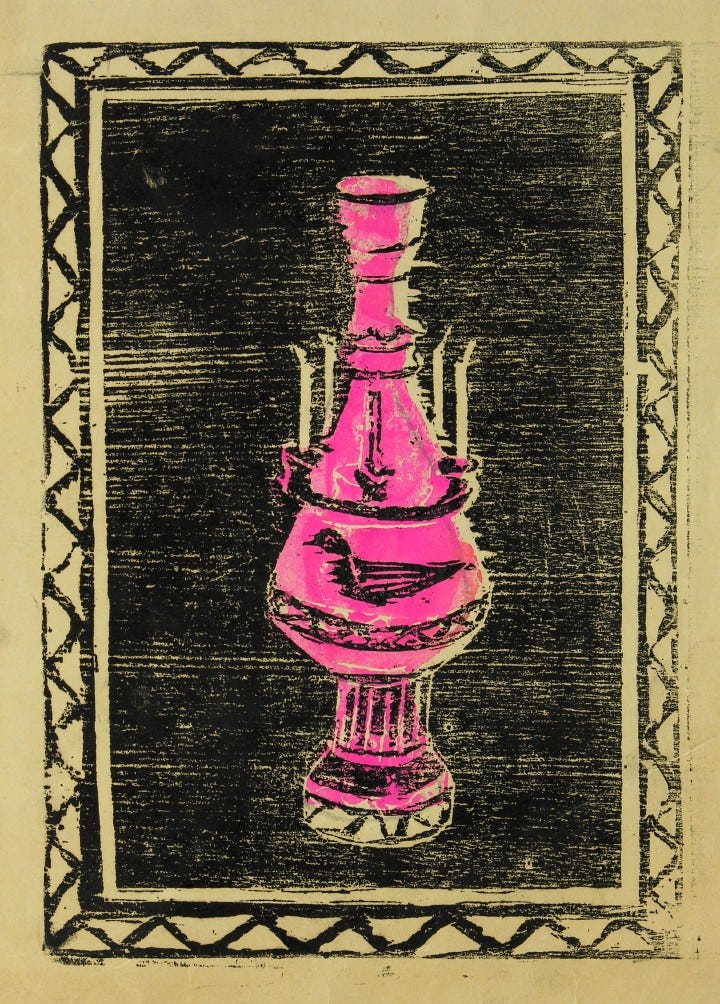

My grandmother was among those artists, as she discovered her love for etchings while studying at the Slade School of Fine Arts in London during the 1950s. She quickly distinguished herself by winning the Slade Prize for Etching in 1955, her final year at the school. When she returned to Cairo, she experimented with various other forms of printmaking, including lithography and woodcuts. Her woodcuts, rarely seen or exhibited, offer fascinating insight into an artist experimenting with a medium she would soon come to master.

While she would continue to paint and experiment with printmaking for the remainder of her career, etchings made up the vast majority of her output. It was through this medium that Helmy distinguished herself as a pioneering artist. She won the Cairo Exhibition Prize in 1957, and two consecutive Salon Du Caire prizes in the early 1960s—all for etchings.

Helmy represented Egypt and the graphic arts on the international stage. She was particularly active in Yugoslavia, having displayed her work at the Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts at least eight times over the course of two decades—more than any other Egyptian artist. Helmy also received an honourable prize from the Ljubljana Organizing Committee for an etching exhibited during her first appearance in 1961. Her continued distinction at the biennale led to her being named an honorary professor at the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno in Florence in 1963.

Helmy continued to find success abroad, participating in numerous international biennials across West Germany, Poland, Italy, Japan and India. She even participated in four consecutive editions of the Norwegian International Print Biennale starting in 1978. By 1980, Helmy’s etchings were on display at arguably the most famous biennial of them all: the Venice Biennale. The following year, she was awarded a lifetime achievement award—the National Merit Prize for Etching—by the Egyptian state for her pioneering work in the field.

Despite accumulating accolades and international acclaim, Helmy’s work fell into obscurity following her passing in 2004. Even the works donated to the Egyptian state were left to accumulate dust in the storage facilities of the country’s various museums. While much has changed in the years since the Menhat Helmy Estate was established, if you were to visit the Museum of Modern Egyptian Art in downtown Cairo today, you would only find her paintings on display—not the etchings. While the painting is a stunning work of geometric abstraction, it is an incomplete representation of her oeuvre.

Helmy dedicated herself to a medium that required patience, precision, and an avant-garde approach to experimentation. Her etchings ranged from high modernism, which won her acclaim at Slade and at exhibitions in the Western world, expansive cityscapes brimming with life and character, to complex multi-plate geometric abstraction rarely seen before in the medium.

Thankfully, Helmy’s prints are once again being restored to their rightful place in the pantheon of modern art. A selection of her abstract prints were displayed at the groundbreaking Konkret Global exhibition at the Museum im Kulturspeicher Würzburg, Germany in 2022. Others were exhibited at the Art Cairo show at the Grand Egyptian Museum earlier this year.

This is a step in the right direction and gives me hope for the future—one where Helmy’s prints are as sought after as her paintings, and where the depth of her practice is publicly available for all to appreciate.

The Art of Menhat Helmy is a newsletter and platform supported by its readers and managed solely by the artist's family. Our goal is to persist in showcasing Helmy's groundbreaking artwork and to inspire emerging Arab artists.

If you haven't already, we encourage you to consider becoming a paid subscriber.

This is an excellent article, Karim. As a Fine Arts graduate and artist, I can fully appreciate everything you’re telling us. I knew your grandmother was a printmaker as well as a painter but didn’t realize the back history and context of her work. A revelation to see it. Thank you for this and keep these articles coming - I learn something every time I read them!

And also liked your writing about Edvard Munch. One of my favorite artists - I almost think his prints are stronger than his paintings. I think colour alters the perception of an artwork. Black and white can be more impactful than when colour comes into play - I’ve always liked doing drawing for its own sake. (Although of course I enjoy colour too).